In this section

In this sectionAccording to UNHCR, 110 million people and more than 1 in 73 people around the world are forcibly displaced. The majority, almost 9 out of 10, live in low- and middle-income countries. Climate change is one of the reasons for displacement, and climate-related disasters are affecting both displaced populations and host communities. It is, therefore, important to enforce climate action in global displacement contexts and let the displaced meaningfully participate in climate adaptation, mitigation, and resilience efforts.

However, global climate-making spaces and events continue to disregard the meaningful participation of displaced persons. For instance, the under-representation of displaced persons in high-level decision-making spaces on matters that affect their lives has been one of the major concerns of this population. The Conference of Parties (COP) 28 hasn’t brought a significant impact on the representation of the displaced persons. COP28 is one of the biggest events in its history, with 100,000 delegates, 190 nations, and 140 world leaders expected to attend; the delegation of forcibly displaced persons was a drop of water in the ocean with less than 10 people with displacement backgrounds who attended.

This under-representation is equivalent to 0.01%, whereas the ideal representation given the ratio of the displaced (1 in 73) would be 1.40%. Such a glaring absence of displaced persons at COP28 dents the principles of inclusivity and participation that are essential for effective decision-making and policy formulation. The more these voices are excluded, the further we risk perpetuating a top-down approach that fails to consider the diverse perspectives and needs of those directly affected.

The ultimate goal of COP28 was to set up mechanisms that ensure the reduction of emissions and increase adaptive measures to respond to the substantial impact of climate change and extreme weather events that have already started affecting people. A process that involved rounds of negotiations between parties to ensure the outcome reflected everyone's desires. The following points were at the centre of various conversations: Fossil Fuels & Clean Energy, Loss & Damage, Adaptation, Climate Finance, National Climate Plans (NDCs), Food, Cities, Methane and Forests & Land Use. The call to transition to clean and renewable energy, for instance, attracted commitments from 130 countries to work towards ensuring they double their energy efficiency efforts by 2030.

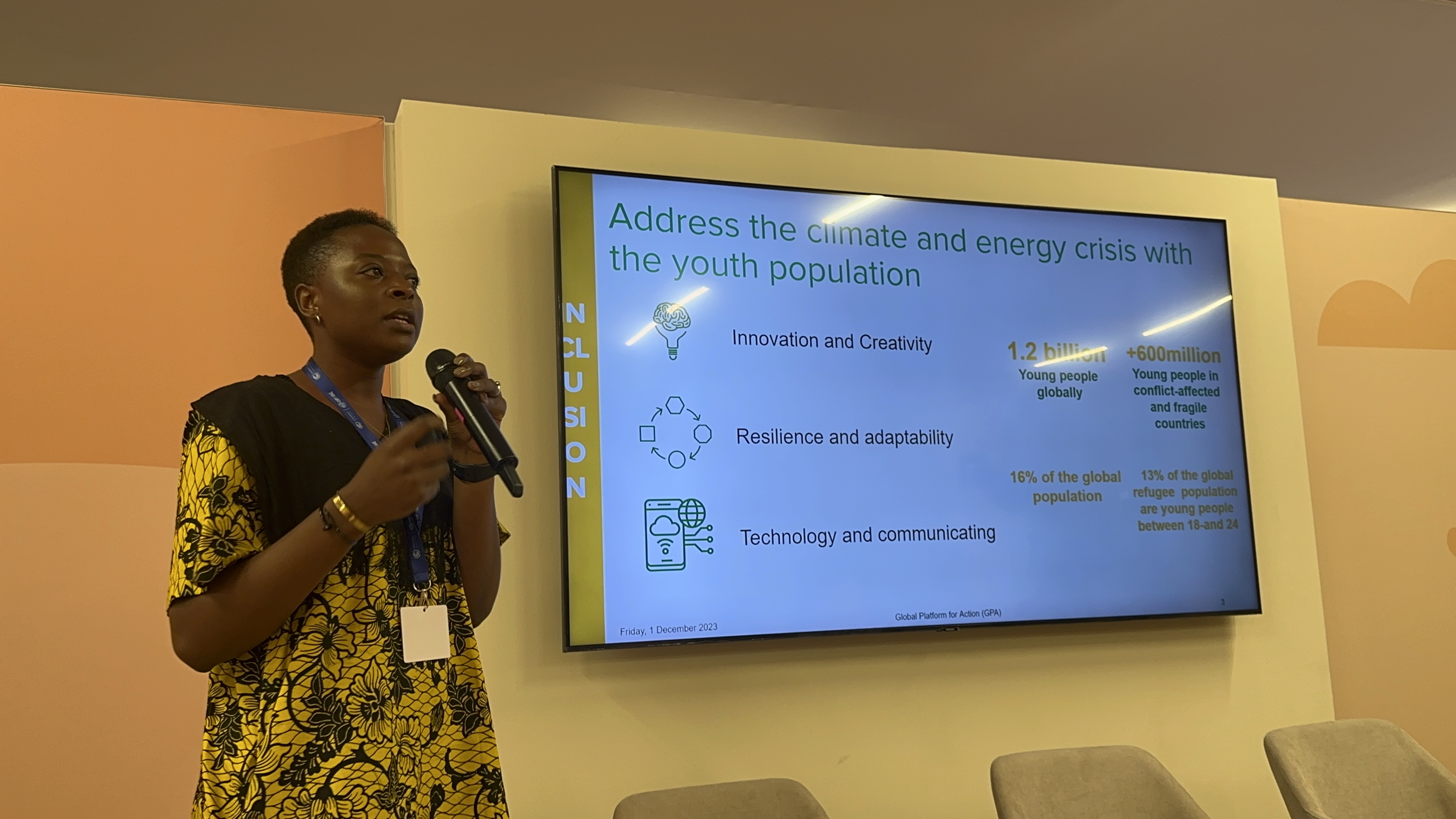

Various thematic areas, including but not limited to health, food, energy, etc., with four major cross-cutting themes: Technology and innovation, Inclusion, frontline communities, and finance, guarded different conversations at COP28. Different organisations, such as the Global Platform for Action on Sustainable Energy Access in Displacement Settings (GPA), UNHCR and IOM, held side events to discuss unique challenges and valuable inputs displaced people hold in the context of climate response strategies. The need for inclusive approaches was translated to a shift from traditional humanitarian to a more inclusive humanitarian response where the role of refugees and other displaced persons are considered key actors and not merely recipients of aid. Moreover, the emphasis on breaking barriers between displaced persons and substantial stakeholders such as donors was strongly highlighted across different conversations to ensure the real needs of the displaced person are known and effectively addressed.

The COP28 declaration on climate, relief, recovery and peace sealed the effort of many by dedicating a paragraph that encouraged the pledge signatory members to promote their leadership and inclusion in the climate action. Pledges at COP28 are very high level; their translation in terms of implementation and practicality based on context, capacity, and resources is still something to work on as often countries hosting refugees operate with tight resources with high demand.

The announcement of the loss and damage fund, where more than USD 700 million was pledged from high-income countries such as the UAE, Germany, the UK, and the US as a mechanism to support countries, mostly low- and middle-income states who are the smallest contributors to climate change but the most impacted by extreme weather events. The presence of this funding necessitates a fund distribution mechanism that would encourage the flow of resources to reach displacement settings. Ensuring the funding goes beyond addressing the occurring causes of climate change in displacement communities but enables them to build the capacity, adaptive measures, and resilience needed to address the impact of climate in their settings.

The disproportionality of the impact of climate change across the globe, where the leading CO2 emitters are less impacted and better prepared to respond to the impact of climate change while countries at the other end of the scale pay the greater price. This situation worsens the vulnerability of the displaced persons as they are the last priority of the countries hosting them, often hosted in low- and middle-income countries where around 90% of the world’s displaced population reside, according to UNHCR. Therefore, it is imperative to develop and reinforce clear and inclusive strategies that ensure the world’s displaced persons are not left behind in the energy transition efforts and in the pursuit of access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all. Putting the displaced communities at the front line of addressing the impact of climate is a core strategy in ensuring the challenge is addressed effectively. The profound understanding of the context and valuable skills from the displaced and host communities are essential in addressing the climate issue that affects their lives and livelihoods. Therefore, allowing programming to be tailored and led by the displaced communities, where local solutions are equipped with adequate resources to effectively address the challenges they are facing, is a step forward to developing contextually appropriate and culturally relevant climate solutions that will stand the test of time and achieve sustainability.

However, it is painful and non-realistic that the global spaces where very critical decisions are taken, such as COP events, are still inaccessible spaces for displaced persons. For a few who can make it, their presence is not strong enough to influence the decisions, bilateral agreements, and funding appropriation thereafter. The culture of speaking on behalf of refugees and displaced still prevails regardless of continuous push from refugees and other displaced people to be given a space at the table to speak for themselves. A point that Joelle Hangi made on behalf of the GPA at COP28: “We don’t need translators anymore; we can speak for ourselves”. The need for more inclusion of refugees and other displaced in decision-making spaced is still a puzzle missing in the bigger picture. The current status of displaced population inclusion in global policy-making spaces is cosmetic at best and does not include influential powers to determine the fair share of burden, resources, and responsibilities for global displacement settings.

The international arenas like COP28 and their commitments towards addressing climate change should place more focus on including the directly affected communities in the policy discussions. In the end, more inclusive approaches and mechanisms are what matters to ensure a just and equitable climate response where the most affected population, including refugees and other displaced people, are equipped with the necessary capacity and resources to help them respond to the climate change that is painfully affecting their lives.

The blog was written by Joelle Hangi & Epa Ndahimana as part of the deliverables of Transforming Humanitarian Energy Programme (THEA) funded by the UK government's Transforming Energy Access (TEA) programme.

Last updated: 22/12/2023